This is Part Three of our Four Part Series: Restore the Earth Dispatches from China.

To read Part One, click here.

To read Part Two, click here.

The Three Gorges Dam

Dispatches from China: Part Three

The Yangtze River and the Finless Porpoise

We have been fascinated by the story of Ai Luming, the founder of the Changjiang Conservation Foundation, who swam the Yangtze River when he was 23, over 30 years ago. Along the way he was playfully followed by many different pods of finless porpoise, native to the Yangtze and now endangered.

The river’s present degraded state and the disappearance of the porpoise were the initial motivation for Ai Luming to establish the Foundation, so we were eager to see it for ourselves and to discover the source of his passion for conservation.

The Yangtze is the “Mother River” of China, of critical geographic, ecological, cultural, and economic importance to the country. The Yangtze watershed touches 19 provinces and is central to the lives ofmore people than the total populations of Russia and the US combined.

Much like the Mississippi splits the US into east and west, the Yangtze divides China into north and south. It begins on the Tibetan Plateau and ends in its delta at Shanghai and the East China Sea, about 4,000 miles away.

North of the river are wheat fields and coal mines; along its southern banks grow rice, tea, cotton and timber.

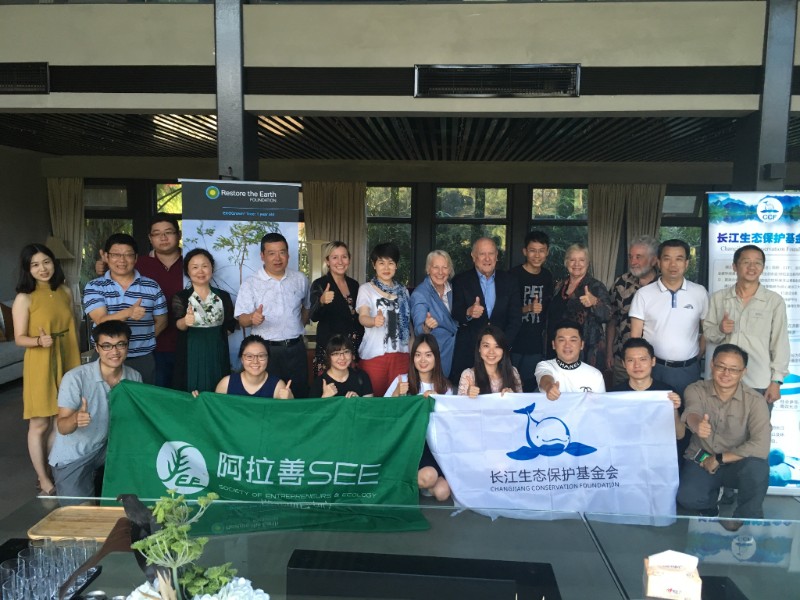

Our trip to the Yangtze began in Wuhan, the sprawling capital city of Hubei Province, which straddles the river in central China. We were guests of our partners, Changjiang Conservation Foundation (CCF) and its sister foundation Alashan SEE Foundation (Society of Entrepreneurs & Ecology).

Flying into Wuhan, you see miles and miles of high-rise condominiums surrounded by lakes and rivers.

Wuhan is a city with both an ancient history and a thriving present. Historic relics excavated from ancient tombs tell the city’s long history, dating back 3,500 years. Starting here, merchants followed the great Yangtze and lake network to expand businesses throughout the entire country.

Wuhan where the Han River meets the Yangtze River

Wuhan sits on the Jianghan Plain, a river-crossed fertile land created where the Han River joins the Yangtze River. The city is surrounded by water: lakes like the beautiful East Lake, and wetlands. Wuhan’s wetlands play a significant role in the sustainable development of the urban eco-environment. Accelerated urbanization since 1980 has caused rapid changes in urban wetland landscape patterns, seriously affecting the wetlands’ healthy functions.

The wetlands around Wuhan are also a migratory bird paradise. Wuhan is one of the three migratory flyways in China. Fertile wetlands in Wuhan provide migratory birds with the necessary environment, food chain, and conditions to thrive. From November to March, Siberian winds carry thousands of migratory birds south to Wuhan on their way to India and Africa for the winter.

The Alashan SEE Foundation arranged for a visit to the Fuhe wetlands, one of five natural restoration and protection zones designated to protect bird habitat for over 20,000 birds.

Fish and shrimp living in the wetlands supply the food for bird species including bean geese, graylags, swans and an endangered Euraisan spoonbill and diving duck – the Baer’s pochard – found in eastern Asia. We spotted a Baer’s pochard while in the recently restored area.

The Alashan SEE Foundation was established in 2004 as the very first private entrepreneur business leaders group in China. Its more than 1,000 entrepreneur members take social responsibility seriously, treating it as their personal obligation to promote sustainable development and protect the environment. The Fuhe wetlands is one of the Foundation’s many projects across the country.

Yangtze River’s Finless Porpoise

The Yangtze is the world’s third longest river and was once thought of as “China’s Amazon” – a place of great biodiversity. Among its natives is an ancient species called the finless porpoise, the only subspecies of porpoise that lives in freshwater – a symbol whose fate is believed to reflect the river’s health.

Saving the finless porpoise from extinction is another Alashan SEE Foundation initiative. Without intervention, it is believed that the finless porpoise will disappear within the next five to ten years.

The Chinese people have always lived in harmony with finless porpoises. The porpoises were often worshipped as river goddesses by fishermen, as they seemed to be able to know the weather beforehand. People believed that seeing a Yangtze River porpoise was a good omen that foretold a peaceful trip. However, the process of industrialization has reshaped China’s whole landscape in an unthinkably short period.

Views from the Yangtze River

It’s at the Wuhan Institute of Hydrobiology, part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, supported by the Alashan SEE Foundation, that we see the relocation of the finless porpoise, one of the efforts to conserve this endangered species. The Institute includes both indoor and outdoor holding pools, a water filtration system, food storage and preparation facilities, and a research building.

This initiative has three components that are being implemented simultaneously – two located in the Yangtze River, their natural range, and one at the Institute, where the animals are removed from the wild for protection and artificial breeding. The animals bred at the institute are then introduced into a “semi-natural” population in an oxbow, a protected area within the Yangtze River system.

Still another initiative by the Alashan SEE Foundation on the Yangtze, just below the Three Gorges Dam, is a program that retrains and pays fisherman to patrol the river for violations that threaten the finless porpoises, and replenishes the native river fish that were impacted by the building of the dam.

These small steps to conserve this threatened species are meeting with some success. The challenge is to accelerate and amplify these and other actions, like addressing nutrient run off from agricultural production and discharge from industrial facilities along the river banks.

SEE Members with Restore the Earth, CGPI and East-West Philanthropy Forum staff at SEE headquarters in Wuhan

Downtown Wuhan next to Guiyuan Temple

Guiyuan Temple

Our trip to Wuhan also included some cultural and economic revelations.

We made an early morning visit to the Guiyuan Temple, a Buddhist temple in Wuhan, built over 400 years ago, in 1658, as the first Zen Temple in Hubei Province. “Guiyuan” in Chinese means achieving sainthood and becoming a Buddha. Inside this temple is a special place with many works of art, drum and bell towers, temple halls with a number of valuable preserved Buddhist images and stele (stone slabs), and the Lotus Pond with prized turtles. Recently, when the head priest of the temple died, so did all the turtles in the pond – on the very same day. It was even reported in the local news!

The temple’s Arhat Hall contains 500 gold-painted wooden statues of Buddhist monk-saints. No two are the same. Legend has it that the two sculptors employed on this task took nine years to complete it.

Every “light lunch” and dinner we had in China was a grand affair, with big round tables that had revolving “lazy susans” with literally a dozen or more dishes to choose from. During our entire three weeks in China, we were not served the same dish, ever. Each and every offering was exquisitely made of the freshest ingredients, and was cleverly seasoned, prepared and presented in the most innovative and creative ways.

Beautiful lotus dish display

Lotus was in high season, so we ate it in many forms: lotus root slices that were fried like potato chips, in soup with pork and chicken, marinated, as well as lotus petals and popped lotus seed pods as snacks. All varieties were nicely seasoned and delicious!

Our last night in Wuhan was hosted by our partner, Ai Luming, his wife and two daughters, at their private “tea house” on East Lake in Wuhan. Marv especially enjoyed the 40-year-old scotch.

Before we left Wuhan, the new Z Bank arranged a private meeting to share with us their new approach to banking; and Zair, a brand new private airplane manufacturer, hosted a visit to a new facility where they are building the latest in personal planes (the Chinese government has just approved individual ownership of airplanes and is building 500 new private airports across the country).

Yichang

From the Wuhan Hankou Railway Station, we took a high-speed train west to the ancient city of Yichang, China, to visit the Three Gorges Dam and see the finless porpoises for ourselves in the Yangtze.

Yichang, another “small city” of over 4 million people, has the most beautiful broad parkways directly along the banks of the river. We loved seeing how active these lovely parks are, with karaoke singing, fisherman dropping in lines, families out for a walk, joggers and other activities all along the banks of the Yangtze. As we learned, in China there is a mandatory retirement age – for women it is 55 and for men 65. So there are many retirees, and it is a tradition for the grandparents to raise grandchildren while their parents work. We saw these multi-generation families enjoying the recreational areas, parks, and parkways.

We traveled through the mountains north of Yichang on a modern snaking highway to the Three Gorges Dam. The Dam is the largest hydroelectric dam in the world – a 17-year-long $25 billion project that was begun in 1994. It is located in the middle of the three gorges on the Yangtze River. The river in this area historically was wild and turbulent, annually creating disastrous flooding. The Three Gorges Dam was built to control the river, facilitate inland trade, and provide much needed power for central China.

The main controversy around the Dam was the displacement of over 1.3 million residents living in more than 1,500 cities and villages, and the submerging of sites of historical and archaeological importance. But as with any major river project, there were also effects to the ecosystem. The loss of valuable resources and environmental consequences of the Dam have been a threat to animal and plant life due to flooding in some habitats and water diversion in others. Fragmentation of habitat led to disruption in reproductive patterns, resulting in heavy losses in biological biodiversity. And decreases in freshwater flow downstream endangered aquatic populations already threatened by overfishing; led to a loss in sediment and nutrients, causing erosion to the river, wetlands, and seacoast ecosystems; and adversely impacted fisheries and wetland watersheds. All of this added up to a major threat to the finless porpoises.

Recently, the Chinese government mandated the removal of all industrial facilities along the river, mediating the years of impact and degradation to the river system. Also, recent efforts have begun to re-establish native fish species in the river, supporting the health of the remaining finless porpoises.

Following our trip to the Three Gorges Dam, we jumped on a boat that is part of the fleet of the Alashan SEE Foundation river patrol initiative and at sunset spotted finless porpoises successfully surviving in the Yangtze right off the bank in Yichang. We couldn’t have been more thrilled by the sight.

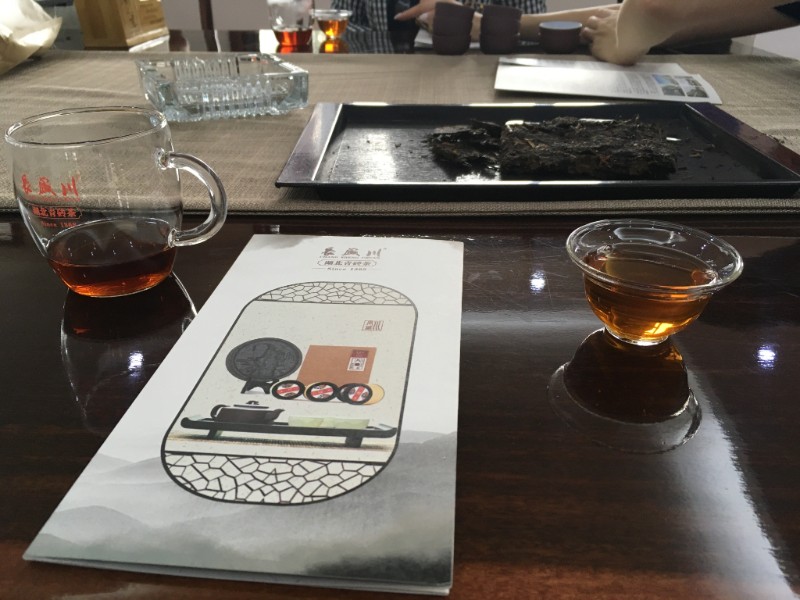

Tea Tasting at Chang Sheng Chuan Tea Factory founded in 1368

Ancient China Tea

Our next adventure, planned by our hosts, was to the Chang Sheng Chuan Tea Factory. This tea company was founded in 1368 by the ancestor of the He family and has continuously operated for over 600 years by 19 generations of the same family. The 20th generation is presently in training.

Its teas were part of a tea shipment that was thrown overboard at the Boston Tea Party. The Chang Sheng Chuan Tea Factory is the originator of chin-brick tea, with the “Red Dragon Certification” granted by the Qing Dynasty, known as “the treasure of the tea road.”

In ancient China, the tea brick (compressed tea made of ground or whole tea leaves pressed into a block using a mold) was the most popular form of tea produced and consumed. It was also used as a common currency for trade, or tributes, outside China.

We learned how to properly make Chinese tea in a “pottery” tea pot only. We also tasted citrus tea, made from a tea-filled dried mandarin orange, where the orange serves as the diffuser – delicious!

But as with so many of the sites we visited, this ancient enterprise is also being threatened by changes to the environment. The company’s tea trees and mandarin orange crops are located all along the Yangtze. So the company is addressing nutrient run off from its crops into the river and is sharing its concern and solutions with other agricultural producers up and down the river. Very impressive.

We left with generous gifts of a variety of teas and a special embossed medallion “tea brick” honoring partnership and diplomacy.

Traditional Chinese tea bricks

This was Part Three of our Four Part Series: Restore the Earth Dispatches from China.

Stay tuned for the Conclusion: Part Four where we travel to Inner Mongolia before departing China!

Our yurt accommodations in Inner Mongolia